« 78 Mulberry Street »

Sunday, January 17, 2010 at 11:51AM

Sunday, January 17, 2010 at 11:51AM My great grandfather, Vincenzo Cervone, came to the US in 1896, leaving my great grandmother and 3 small children behind in Italy. His eldest son, Gaetano, came to New York in 1903 accompanied by Cesidia Cervone Loreto, my great grandfather's sister. In his pocket, Gaetano had the only address I have found for Vincenzo prior to 1906: 78 Mulberry Street.

If you put 78 Mulbery Street into Google Maps, you are directed to a location on Mulberry Street between Canal and Bayard in lower Manhatten. If you then switch to the street view, you will see a tenement in Chinatown which corresponds to this address. But in 1903, 78 Mulberry Street was located in Little Italy, just steps away from the infamous Mulberry Bend.

Jacob RiisGoogle Maps and street view were obviously not around in 1903, but luckily, the area was methodically photographed by Jacob Riis.

Jacob RiisGoogle Maps and street view were obviously not around in 1903, but luckily, the area was methodically photographed by Jacob Riis.

For those of you unfamiliar with Riis, he was a police reporter (turned photographer, turned social reformer) who worked for the New York Tribune and the Associated Press Bureau starting in 1877. During his tenure as a police reporter, he worked out of a police precinct located on Mulberry Street. As a result, his portfolio contains many photographs of Little Italy taken around the turn of the last century. His book, How the other Half Lives, rounds out the picture with (often disturbing and racially tinged) descriptions of life in and around Mulberry Bend.

How the Other Half Lived was orignally published in 1890. It contained an entire chapter on The Bend, which included the picture above. Riis opened the chapter by saying:

"WHERE Mulberry Street crooks like an elbow within hail of the old depravity of the Five Points, is “the Bend,” foul core of New York’s slums. Long years ago the cows coming home from the pasture trod a path over this hill. Echoes of tinkling bells linger there still, but they do not call up memories of green meadows and summer fields; they proclaim the home-coming of the rag-picker’s cart. In the memory of man the old cow-path has never been other than a vast human pig-sty. There is but one “Bend” in the world, and it is enough. The city authorities, moved by the angry protests of ten years of sanitary reform effort, have decided that it is too much and must come down. Another Paradise Park will take its place and let in sunlight and air to work such transformation as at the Five Points, around the corner of the next block. Never was change more urgently needed. Around “the Bend” cluster the bulk of the tenements that are stamped as altogether bad, even by the optimists of the Health Department."

He goes on to the describe The Bend by saying:

"Bayard Street is the high road to Jewtown across the Bowery, picketed from end to end with the outposts of Israel. Hebrew faces, Hebrew signs, and incessant chatter in the queer lingo that passes for Hebrew on the East Side attend the curious wanderer to the very corner of Mulberry Street. But the moment he turns the corner the scene changes abruptly. Before him lies spread out what might better be the market-place in some town in Southern Italy than a street in New York—all but the houses; they are still the same old tenements of the unromantic type. But for once they do not make the foreground in a slum picture from the American metropolis. The interest centres not in them, but in the crowd they shelter only when the street is not preferable, and that with the Italian is only when it rains or he is sick. When the sun shines the entire population seeks the street, carrying on its household work, its bargaining, its love-making on street or sidewalk, or idling there when it has nothing better to do, with the reverse of the impulse that makes the Polish Jew coop himself up in his den with the thermometer at stewing heat. Along the curb women sit in rows, young and old alike with the odd head-covering, pad or turban, that is their badge of servitude—her’s to bear the burden as long as she lives—haggling over baskets of frowsy weeds, some sort of salad probably, stale tomatoes, and oranges not above suspicion. Ashbarrels serve them as counters, and not infrequently does the arrival of the official cart en route for the dump cause a temporary suspension of trade until the barrels have been emptied and restored. Hucksters and pedlars’ carts make two rows of booths in the street itself, and along the houses is still another—a perpetual market doing a very lively trade in its own queer staples, found nowhere on American ground save in “the Bend.” Two old hags, camping on the pavement, are dispensing stale bread, baked not in loaves, but in the shape of big wreaths like exaggerated crullers, out of bags of dirty bed-tick. There is no use disguising the fact: they look like and they probably are old mattresses mustered into service under the pressure of a rush of trade. Stale bread was the one article the health officers, after a raid on the market, once reported as “not unwholesome.” It was only disgusting. Here is a brawny butcher, sleeves rolled up above the elbows and clay pipe in mouth, skinning a kid that hangs from his hook. They will tell you with a laugh at the Elizabeth Street police station that only a few days ago when a dead goat had been reported lying in Pell Street it was mysteriously missing by the time the offal-cart came to take it away. It turned out that an Italian had carried it off in his sack to a wake or feast of some sort in one of the back alleys."

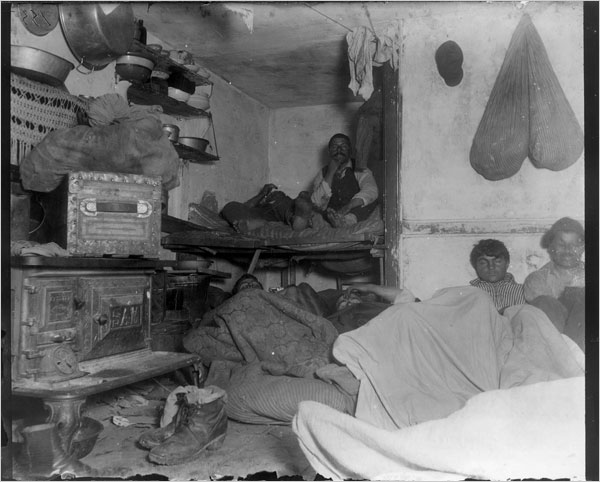

Lodgers in a crowded Bayard Street tenement -- "five cents a spot"

Lodgers in a crowded Bayard Street tenement -- "five cents a spot"

I am unclear how long my great grandfather lived at 78 Mulberry Street, and under what conditions he lived. It is clear, however, that overcrowding and unsanitary conditions were the norm.

The photgraph, shown above, was taken by Riis in a crowded Bayard Street tenement. In the accompanying text, he wrote:

"In a room not thirteen feet either way slept twelve men and women, two or three in bunks set in a sort of alcove, the rest on the floor."

He went on to say:

"Most of the men were lodgers, who slept there for five cents a spot"